On Monday, the Education Research Alliance (ERA) released a new report on the effects of closure and charter restarts in New Orleans and Baton Rouge. Closures and restarts (what ERA refers to as “takeovers”) have been central to New Orleans strategy for nearly a decade.

ERA’s report provides important evidence that when well executed, these two strategies can have strong positive effects on student outcomes. In fact, the report attributes 25% to 40% of New Orleans’ academic improvement to these interventions.

Closure can be even more effective than restarts

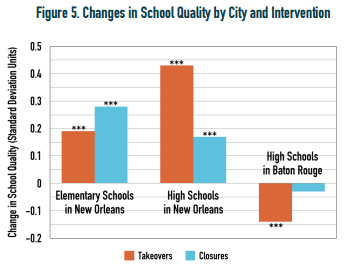

ERA’s research shows that these interventions dramatically improved test scores in New Orleans. The results for closure are especially compelling. Elementary students affected by closures actually experienced stronger positive effects than those in restarts.

Unlike in New Orleans, students in affected Baton Rouge high schools fared no better in closures and far worse in restart schools (graduation and college-going were similarly poor). The authors attribute the differences between New Orleans and Baton Rouge to two factors. First, NOLA closure decisions were focused primarily on the lowest-performing schools in the city. Second, after intervention, NOLA students ended up in higher-performing schools.

Interventions were most effective for NOLA elementary school students

Elementary school students began to benefit almost as soon as the closure or restart announcement was made, and the effects grew more pronounced as students moved through their new school: “affected students…not only caught up with the comparison group but surpassed them.”

The overall effect of these two intervention strategies on elementary school students was incredibly high – somewhere between a 0.3 and 0.4.

High School students also benefited from these interventions

As figure 5 shows, high school closures and restarts also had positive effects (especially restarts). Interventions also boosted graduation rates by 20 percentage points—though college-going rates moved little.

In New Orleans, significant high school reform started more slowly than interventions in elementary schools. Only within the last two years has an open-enrollment New Orleans high school achieved a “B” letter grade (the last year included in the study is 2014). Longer-term outcomes—graduation, college-going rate, college persistence—likely lag behind test score growth. And in the last few years, we’ve seen schools develop programs to support alumni as they transition to college life, that may yield better results for future cohorts of students.

Why these have worked, and what comes next

These results are no accident. The Recovery School District has used a number of policy interventions and direct supports to intentionally move students from the lowest performing schools into much better ones. Quality has driven both closure and authorization decisions, so that restart operators have a high probability of improving performance of the schools they take over. Students in affected schools have received priority placement in OneApp, which has increased the likelihood they enroll in a higher-performing school. NSNO has worked with the RSD and other non-profit partners to provide support to families as they select new schools. And in the case of a recent high school, the RSD placed a veteran education leader in the school to create stability through the end of the school year.

These interventions, along with a more systematic approach to closures on behalf of the RSD, have helped ease the transition for students and families, while ensuring that more kids are going to better and better schools.

But we know can do better. Going forward, we can provide earlier notification to families–possibly even before SPS scores become available–while providing more customized support to help families choose new schools. We can make more funding available to put teams of educators in closing schools to ensure that learning continues through the last day. And for high schools, where 9th and 10th graders are at a high risk of dropping out (whether the school faces intervention or not) we can provide caseworkers to make sure students and their records transfer to better placements so that our most vulnerable kids don’t fall through the cracks.

It is reasonable to ask, given the improvement in New Orleans, whether these interventions are still relevant. Yet thousands of students in our city attend schools performing in the bottom 10% statewide. Closure and restart remain viable interventions for schools that, over long periods, are unable to demonstrate academic improvement.

Over the next two years, as New Orleans unifies under a single governance entity, responsibility for employing these strategies will fall to the Orleans Parish School Board. OPSB has only had to close one charter schools since 2006. If we are to continue the progress of the last decade, OPSB will need to learn from the successes the RSD has had (and the mistakes they’ve made) to make sure that kids in the lowest-performing schools in the city access better placements with as little disruption as possible.

Closures are always going to be difficult. But as the report states, “to the extent that we are trying to improve students’ academic outcomes, our results suggest these interventions can offer promising strategies for improving student achievement when well implemented.”