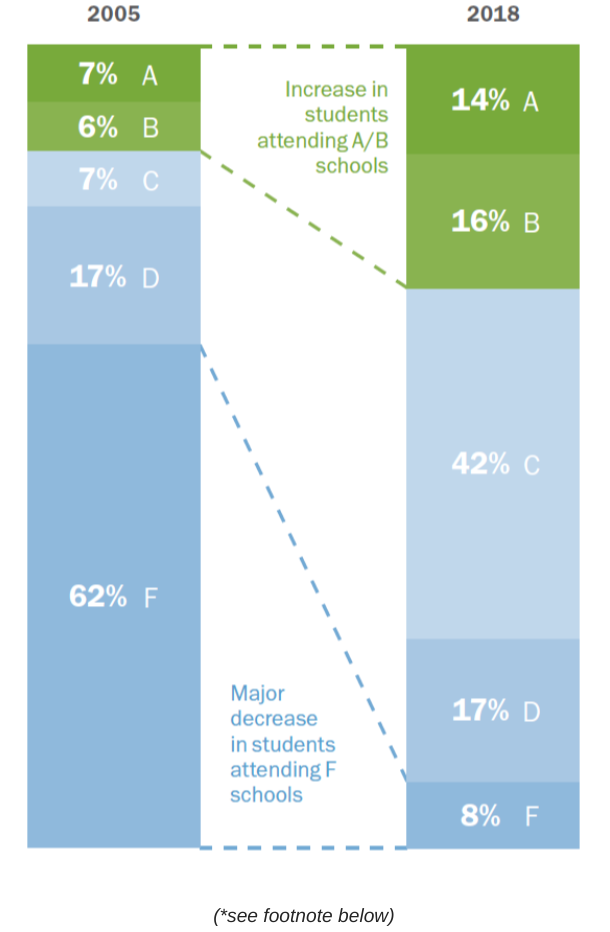

In Louisiana, we have finally given our students the high academic standards they deserve. Over the past decade, in our state, academic standards and assessments have become more rigorous.

As they have done so, New Orleans’ children, teachers, and schools have risen to the challenge. Even as the state’s benchmark for “A” and “B” schools has climbed, the percentage of New Orleans’ schools with those grades is more than double what it was in 2005.

It has been a journey to get here. I have seen much of it firsthand. In 2000, after working as a social studies teacher for almost ten years, I became the Social Studies Assessment Coordinator for the Louisiana Department of Education.

This came at a time of significant change for our education system; Louisiana had just adopted statewide content standards for the first time, and assessments aligned to those standards were in the process of being implemented. Before this moment, different parishes and schools had different ideas about what success meant. Reading The Cat in the Hat fluently could have been a goal for beginning-of-year first graders in one district and end-of-year second graders in another.

So, the Louisiana Department of Education and the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education made changes to address the discrepancy. First, we developed standards in collaboration with a diverse committee of teachers representing many grade levels and parishes. Together, we settled on the academic content that each child in Louisiana should know by the end of each grade. Then, teams like mine worked to create tests that helped students demonstrate that knowledge. We called the test the Louisiana Educational Assessment Program for the 21st Century, or LEAP 21.

It was a powerful tool. By using it, we could make sure that “mastery” of content in one place meant the same thing as “mastery” in another. We could also see how much students had left to learn in order to meet the new standards.

This shift allowed schools and districts to have real measures of student understanding—and, as years passed by, growth. It also made injustice plain. The testing data showed that students of color and students in lower-income areas were not getting the same education as their white or more affluent peers. Such data fueled momentum for tackling that inequity head-on.

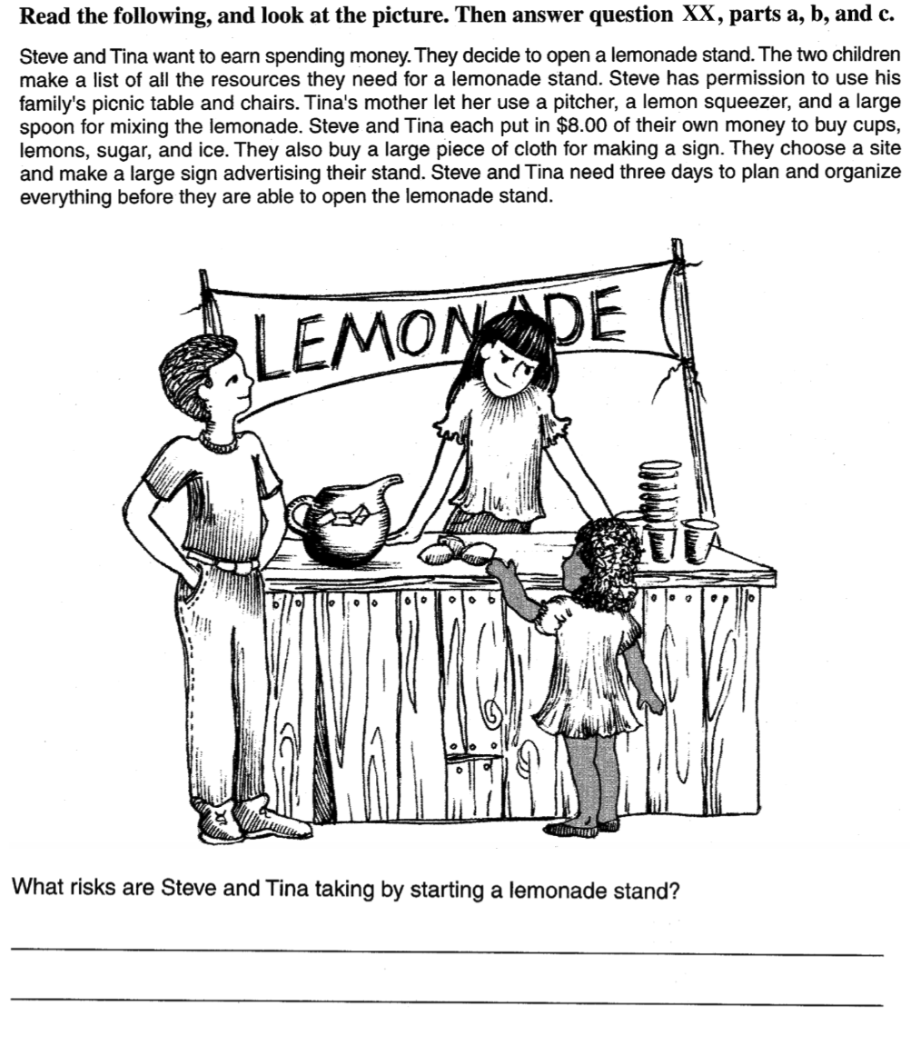

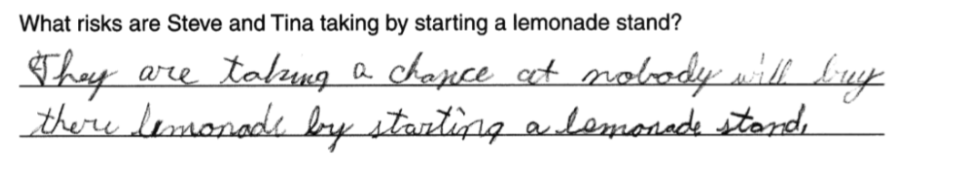

That said, the process was not easy. We were constantly called to rework and revise. One vivid memory I have of such a situation centers around a single test question. In the early 2000s, our state’s fourth graders were given a long-answer prompt, aligned to the grade-level social studies standard about economic risks and rewards. The prompt described a scenario in which two children are opening a lemonade stand; students were asked to identify the risks those children would face.

Some children wrote down the “right” answer. These students described risk as buying more lemons and sugar than they needed for the number of customers that walked by, or making more lemonade than they needed. This answer would earn them four out of the possible four points.

Other students found different risks. These students named the risk of getting mugged once they earned their lemonade money. They noted their lemons could be stolen before they even began to sell. Some students wrote the real danger was standing in front of their home at all.

In our initial plans, this answer would have been labeled as wrong. But as the testing forms rolled in, we realized it was our rubric—not their answers—that was flawed. Students had pointed out very real risks, both physical and economic. So we adjusted the scoring rubric to ensure answers that reflected these real-world responses would count, and could earn four out of four, too.

What could have been narrow-sightedness was actually a chance to innovate and improve. Not only did we adjust the rubric so that students received credit for both types of answers, we also learned a valuable lesson about the range of perspectives our students hold.

That same spirit of thoughtfulness, innovation, and growth has fueled the shifts to higher standards and rigorous curriculum in recent years. Now, our standards set the higher expectations necessary for students to be ready for the demands of today’s colleges and workplaces.

The shift has been critical. It has also, at times, been difficult.

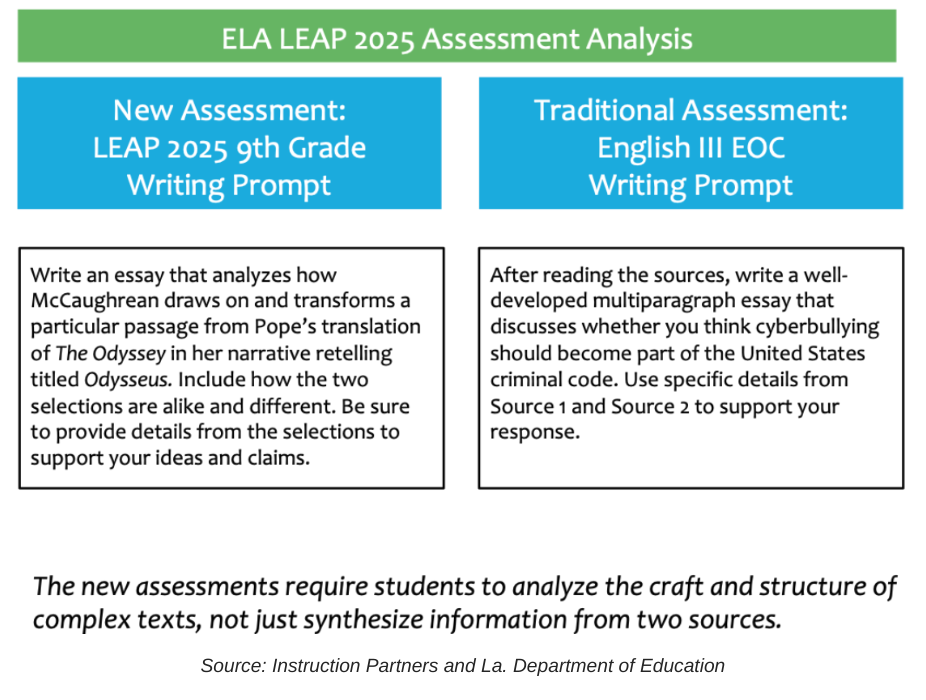

After Hurricane Katrina, student outcomes in New Orleans grew significantly across many measures, from state test scores to high school and college graduation rates and beyond. When we examine outcomes in the years since the shift to more rigorous standards and assessments intensified, however, results are more varied.

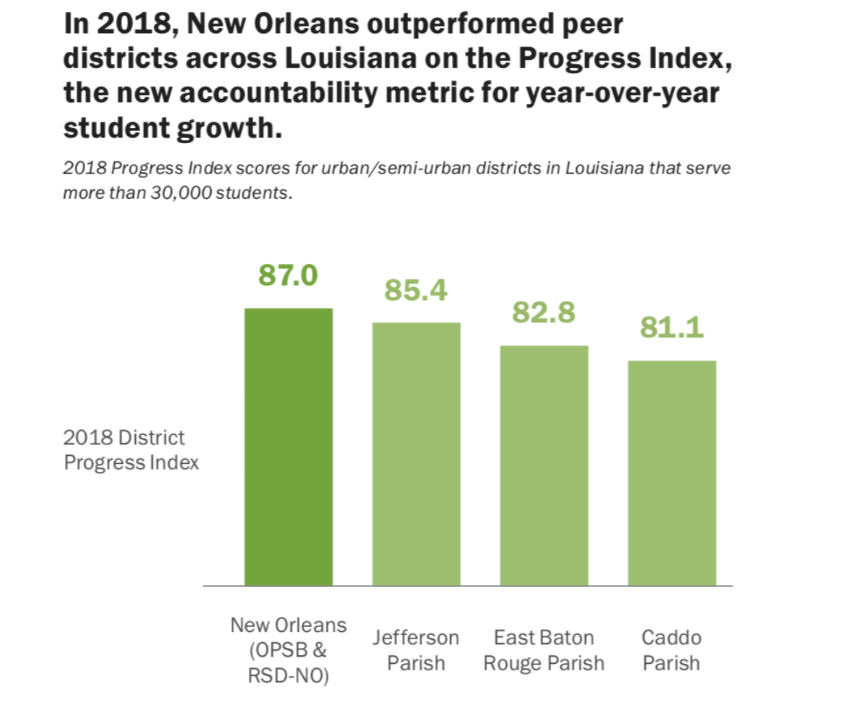

New Orleans stands out for its achievement with Louisiana’s new Progress Index rating, for instance. In 2018, we outperformed peer districts across the state on this metric, which measures student growth from one year to the next.

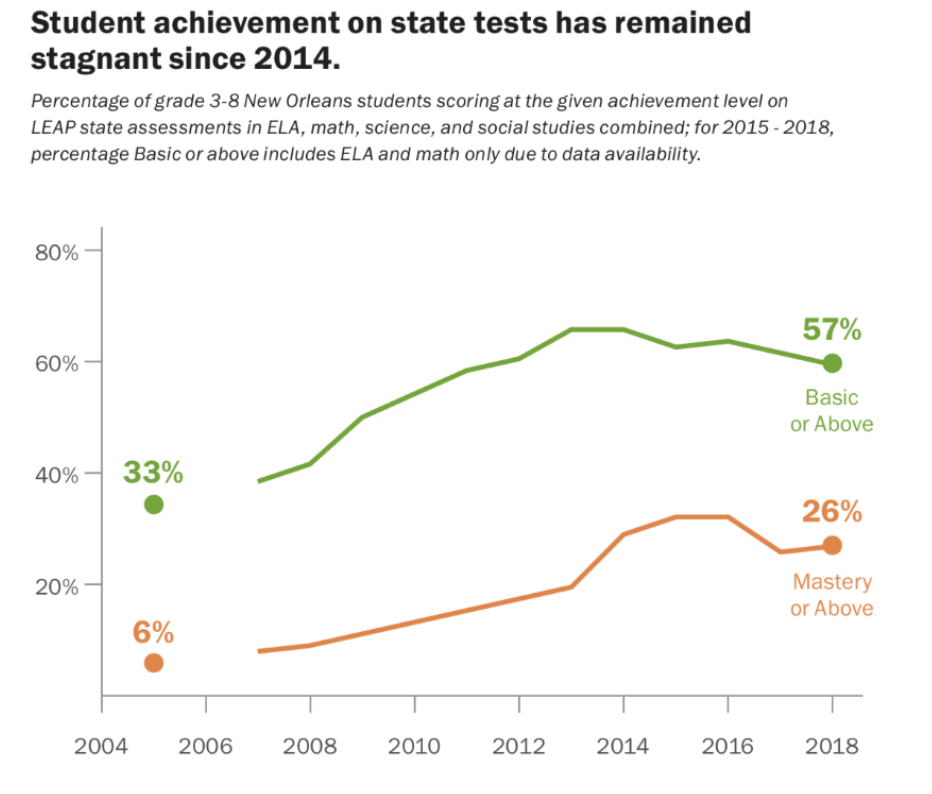

When it comes to state tests, we see massive overall growth since 2005, but stagnation in recent years. Between 2005 and 2014, for instance, the percentage of 3-8th graders earning “Mastery or Above” on their LEAP tests more than quadrupled. Since 2015, however, when the assessments more fully transitioned to the new level of rigor, that growth has stalled somewhat as students and teachers have worked to adjust.

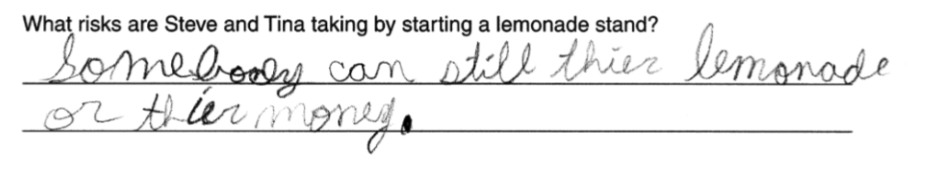

The increased rigor of the new Louisiana standards and assessments is more complex than simply being a harder version of their predecessors. They require students to understand deeply, with more critical thinking, analysis, and evaluation; to explain their thinking and provide evidence for their answers; and to integrate their learning across disciplines, which better reflects real-world challenges and solutions.

This is complex and challenging work, but we are making progress. With the help of NSNO’s Instructional Quality Initiative (IQI), for instance, more New Orleans schools are using curriculum that will truly help students meet standards. Between 2017-18, under 30% of open-enrollment schools used “Tier 1” curricula that the state has deemed as high-quality and aligned to state standards. In the school year to come, over 80% will have adopted it. Shifts like these are important, but take time and hard work to show their full impact. This means any slowed growth is not a reason to return to the way things were; it is why we must keep going.

With the NBA playoffs coming to a close, I think back to debates I had with colleagues in 2000. Back then, they said the tests were too hard and the bar was too high. So I shared this analogy with them: if this were basketball, that perspective meant they would have called just hitting the backboard with the ball a win. We needed to dream bigger and expect more. I am so proud we are no longer telling students it is good enough to simply take a shot. Taking a shot matters, but we do not become educators to show children how to almost-succeed. Instead, we show them how to put it through the hoop, and then expect it. We aim for reverse layups and three-point shots at the buzzer. So we must keep working for the resources to educate them well, with more urgency than ever before. We must help them meet the high standards they deserve. The stakes are high, and our students will win.

*A small number of schools receive “no score in a given year if they are new, recently transformed, or do not yet serve tested grade levels (3-12); in 2005 and 2018, 1% and 4% of students attended such schools, respectively. In 2005, the La. Dept. of Education (LDOE) classified school performance using a star rating system. According to LDOE, ratings from the old star system and the current letter grade system can be compared as follows: 4-5 stars = A, 3 = B, 2 = C, 1 = D, 0 (“Academically Unacceptable”) = F.