“I felt like I was on top of the world.”

Dai’von Floyd’s journey from student to teacher at KIPP New Orleans Schools

Two years ago, Dai’von Floyd was a KIPP New Orleans student. Now, she’s teaching KIPP New Orleans students. And in three years, when she graduates from the University of New Orleans, she’ll be headed back to a KIPP school as a full-time teacher.

Floyd, a graduate of Booker T. Washington High School, is a rising sophomore at the University of New Orleans. Inspired by her high school educators, she is pursuing a career as a teacher. Floyd is part of KIPP New Orleans’ Alumni Teaching Force program, which prepares KIPP upperclassmen and graduates to return to their schools as educators after college.

The first step in Floyd’s journey was taking KIPP’s Education I class while in high school. This included classwork on culturally responsive teaching pedagogy and hands-on teaching experience. The Alumni Teaching program also offers support through college, more experience teaching as an undergraduate, and a teacher residency through an alumni’s first year of employment at KIPP. (The latter aligns with new state regulations that new teachers must have a full “residency” year before leading a class on their own.) Students are also supported in earning their master’s degree.

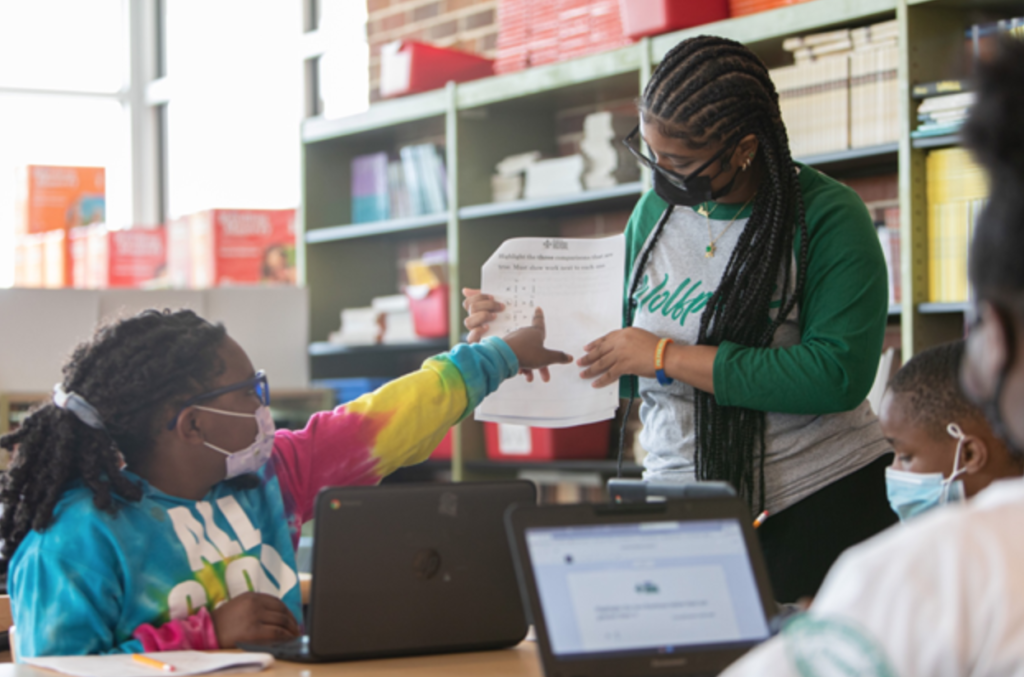

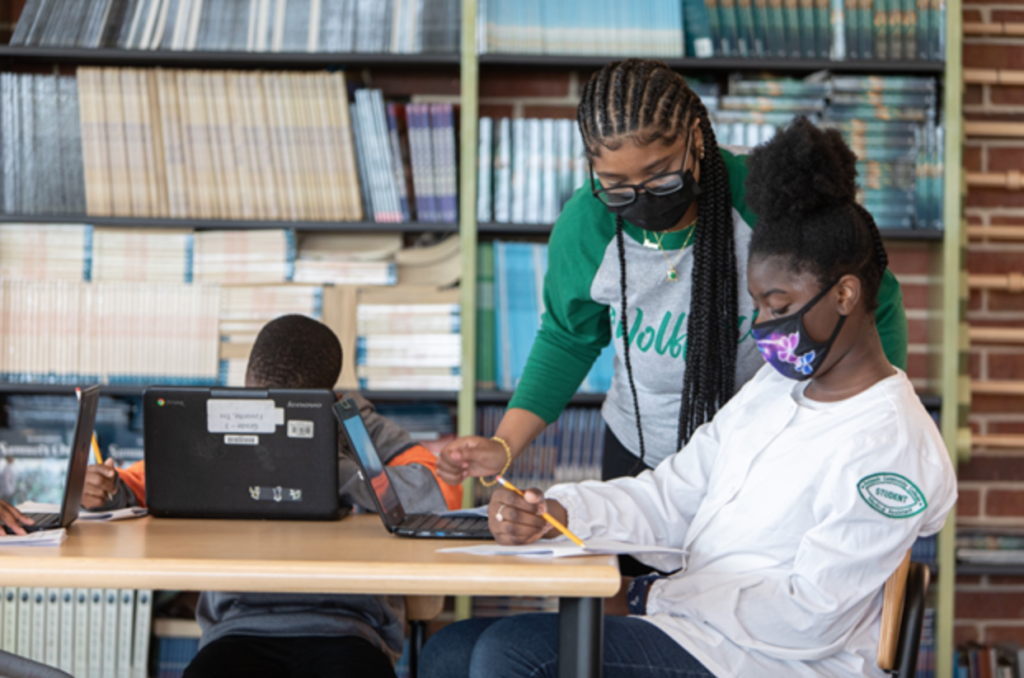

This summer, as part of the program, Floyd has been supporting veteran educator Ms. Nickie Coleman at KIPP Morial Elementary School. Floyd exudes skill and compassion while in the classroom. When she walks up to a student’s desk to help them with their work, she bends to meet them at eye-level. She nods as they speak. If they show her an answer, she asks them how they got it. If they are confused, she asks questions that guide them to an answer. Children are eager to show her what they’ve learned.

Floyd was nervous about her summer placement at first. She struggled with math growing up, and now she was helping teach it.

“I didn’t feel comfortable walking around and helping students out, especially in math. The first student I sat with and helped, I didn’t know if he was picking it up. I was trying my best to explain, but I felt like I wasn’t explaining it well–sometimes I stuttered,” Floyd said.

But they stuck with it together. “He walked over to me and was like, ‘thank you for helping me’…he appreciated my help, and it made a difference,” Floyd said. “It made me feel proud, because especially in math, a subject I struggle in, I was able to help him pick it up and understand it more. I felt like I was on top of the world.”

When Floyd thinks about being the lead teacher in her own classroom someday, she thinks about creating space for struggle.

“I know that some students are scared of being judged because they don’t understand something. And, growing up, you know, I was scared to ask questions too…I want them to feel like they can ask the question, and no one will judge them – because a question will lead to everybody’s growth,” Floyd added. “I want it to be a safe space, just very understanding, calm and comforting.”

Floyd found comfort in school growing up, and believes that classrooms can also be a site of healing.

“I felt like learning gave me a little comfort, or maybe made me just a little bit happier. The more you learn, the more you feel smart. So, I feel like it could be healing…depending on the classroom, depending on how you take that experience, you can make your future brighter.”

Before this summer, Floyd had already gained some experience in elementary education. Her education classes at Booker T. Washington included a twice-weekly assistant teaching placement at KIPP Central City Academy (KCCA) where she supported fourth grade English Language Arts.

Floyd attended middle school at KCCA, and had a cousin that was in second grade there at the time. It was powerful for Floyd to be able to teach where she has relatives and where she went to school. She believes teachers who have grown up in New Orleans hold a powerful asset.

“A lot of people see New Orleans as very dangerous, or, rough…if you grew up in New Orleans, you might look at students that some people might see as rough as, like ‘oh, no, they’re just having a bad day. They’re not rough, they’re not mean, they’re not angry,” she said.

She thinks that sometimes, teachers that are new to New Orleans might misinterpret a child’s humor or tone. As someone from New Orleans, she feels equipped to understand her students’ meaning.

“Some people might be like, ‘oh, my gosh, why are you talking to me this way?’ But you know, it might just be the accent, or it might be slang,” Floyd said. “And so, a teacher from New Orleans might realize, ‘oh, they’re just playing, that’s supposed to be a joke.’”

When she imagines her future classroom, she thinks about the educators she had as a student. One of those teachers is Adam Kohler, a history teacher at Booker T. Washington. Floyd struggled in math, which she took right before Kohler’s class. She often showed up to Kohler’s class feeling unsuccessful.

But everything changed one day. Floyd arrived to class and immediately put her head on her desk. Kohler asked her to sit back up and engage with the lesson, but she ignored him. Kohler asked her to step outside the room to chat. Instead of scolding her, he asked how she was feeling. She explained she was discouraged. He listened, then shared his own experience.

“He told me he wasn’t always good at math. He said he didn’t get the best grades in math. And he was like, ‘look at where I am. I’m a teacher. I have a career, not just a job. I’m doing great.’ And that always gave me hope. Like, it doesn’t matter where I’m at, right now. I know my future…I know I want a career,” Floyd said.

Floyd traces her desire to be a teacher back to that moment. It also shaped the type of teacher she wants to be.

“He was like, you can sit out here for a little bit, take some time to regroup, and then come back,” Floyd says. “And, you know, a lot of teachers might be like, ‘oh, that’s detention, or go to the principal’s office…and so that impacted how I saw teaching.”

After that moment, Kohler became a mentor for Floyd. The connection they built was sustaining for her, and she hopes to build those strong connections, too.

“So, whenever I have a bad time, I think about what he told me…even though I graduated, and I’m in college, I feel thankful for that. I probably wouldn’t even think about being a teacher…but I wanted to make a connection, and he made a connection for me,” Floyd said. “I want a student to be able to be like, ‘thank you for telling me that.’ That’s the connection I want.”