Kenneth Johnson is an assistant principal at Arthur Ashe Charter School and was a 2018 New Orleans Excellence in Teaching Award Winner.

Many Wednesdays, JB comes to visit me at Arthur Ashe Charter School, where I am an assistant principal. JB is in high school now, but I taught him when we were both at KIPP McDonogh 15. Back then, JB was a sixth-grade student and I was his math teacher. JB truly struggled. He acted out in his classes and couldn’t seem to focus; nothing seemed to help. I never stopped trying, though. I worked to provide JB with the supports he needed, and sometimes I saw progress, but I wasn’t sure it would stick.

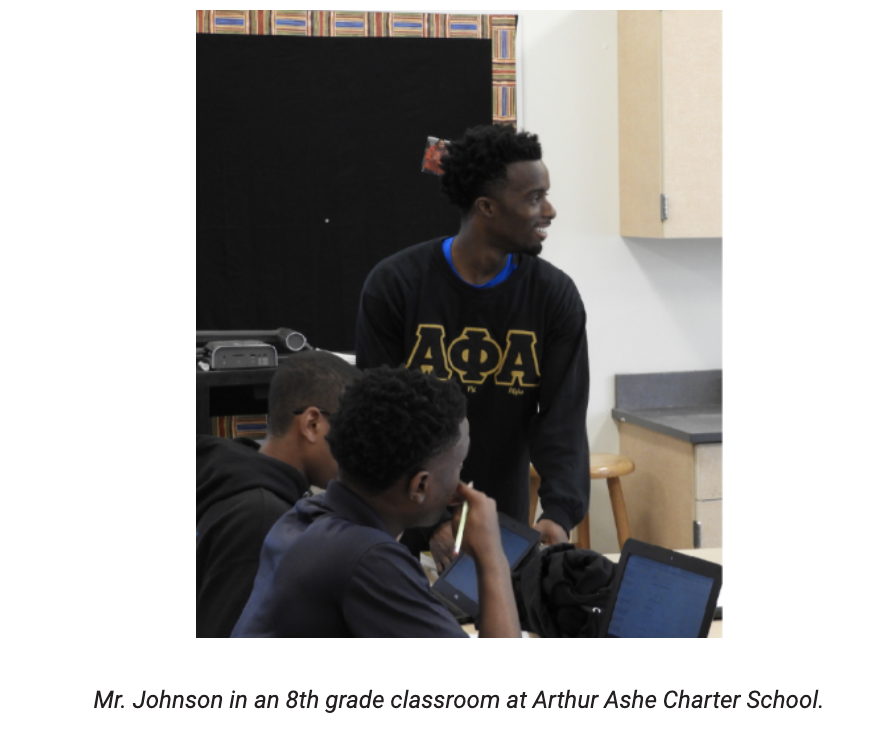

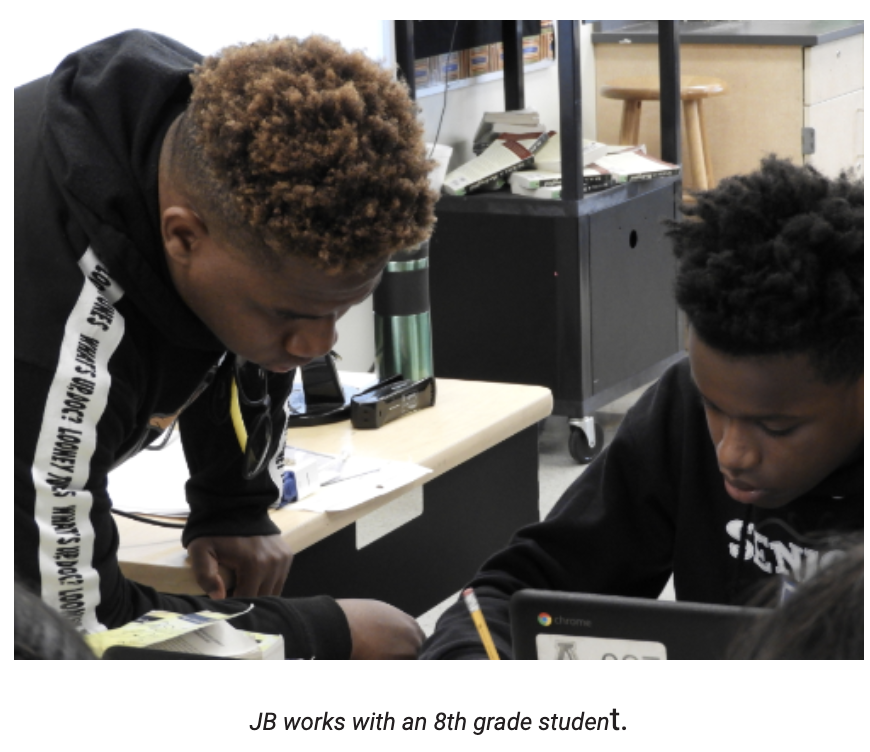

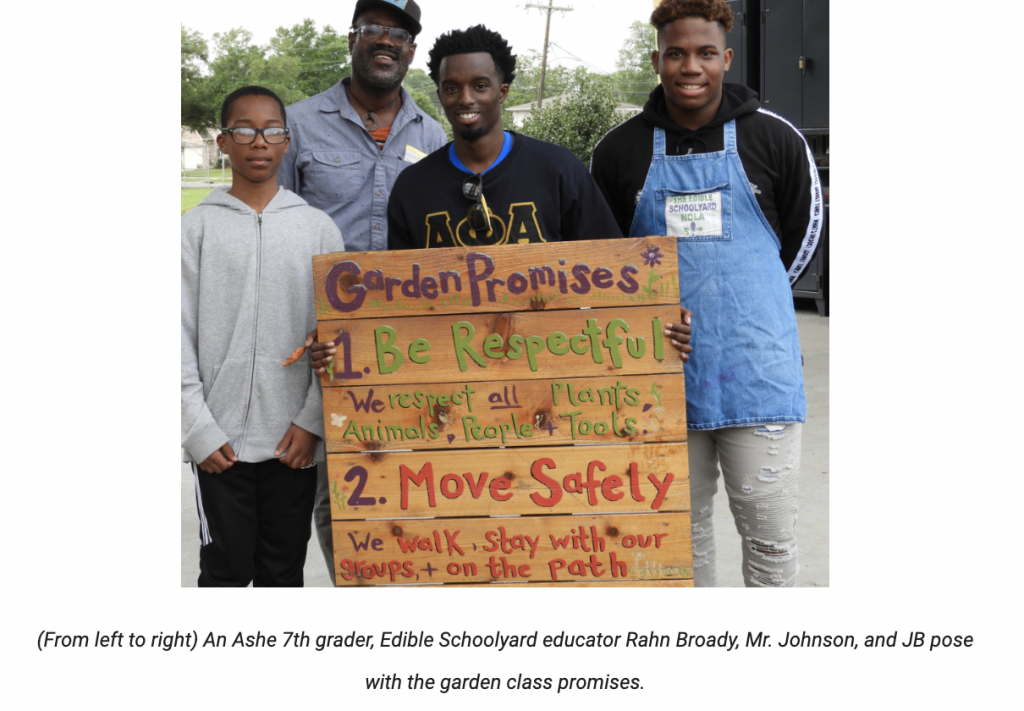

It didn’t happen right away, but these days, JB is on track. He does his homework by my side once a week, then visits Ashe’s reflection space, where students who are sent out of class take some time to reset. He helps the students there with their homework and talks with them one by one.

I listen carefully to what he says; I’m inspired every time.

“Don’t do it like I did. It’s fun to play around, but then your friends move on and you don’t. My friends graduated two years ago and I haven’t yet.”

The students hear him out. JB is older. He’s wise and he’s kind. He doesn’t sugarcoat things. He tells it like it is, and that builds trust. When I work with students, particularly those with different learning needs and exceptionalities, I take cues from JB’s approach.

I also draw from my own experience, growing up as a young black male with dyslexia and ADHD. Together, these qualities created the perfect storm of self-doubt and low societal expectations. I took in messages like “you’re not going to make it,” and “you’ll be ‘the behavior child’ your whole life.” I work to make sure my students don’t receive these same messages.

I want to serve as a role model, both as a black leader, and as someone who overcame their own academic challenges.

As I do that work, I think of my own sixth grade teacher, Ms. Handly. Ms. Handly taught me to self regulate with my ADHD in particular. Other teachers would send me to the corner or try to remove me from class, but Ms. Handly wanted to keep me involved. She let me lie down on the floor to work when I needed to, or walk around the room as I took in a lesson. She helped me focus and learn.

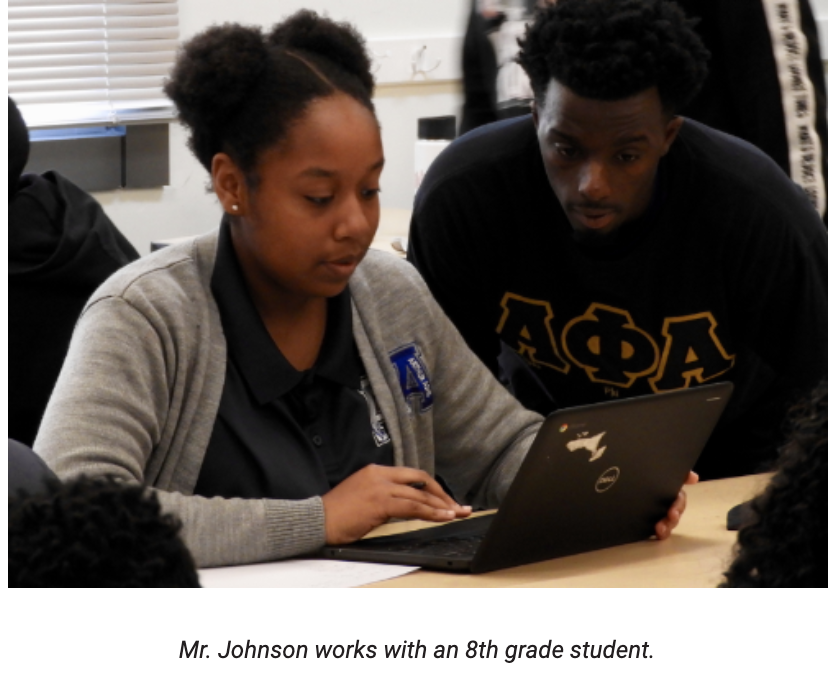

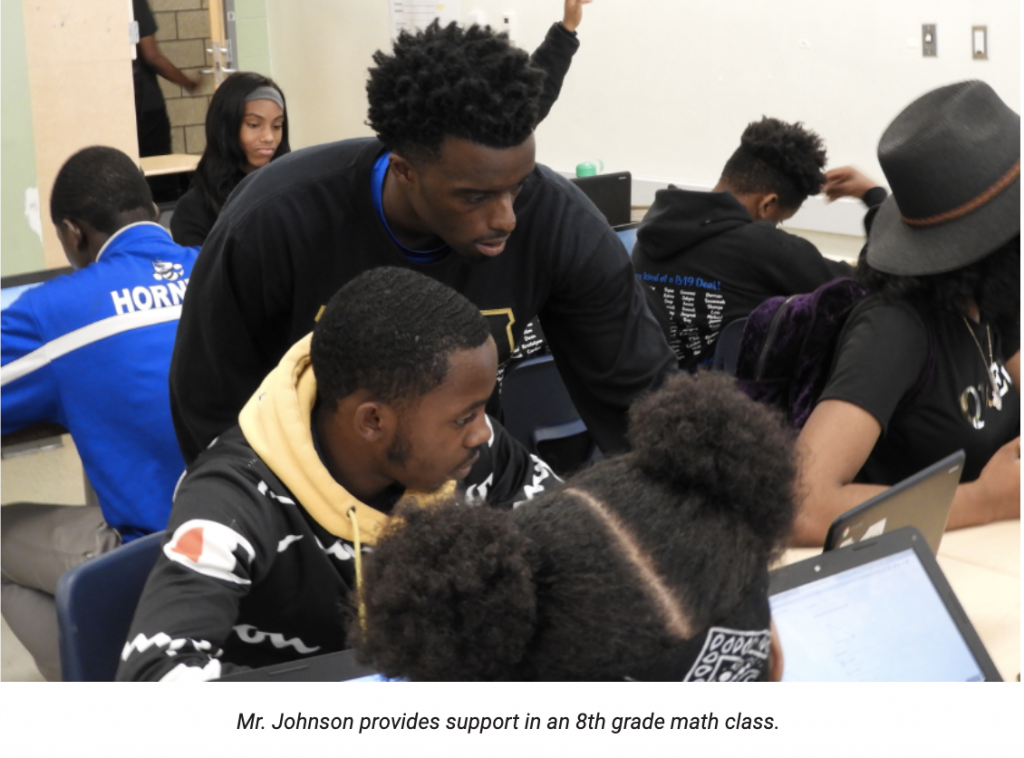

So today, I make sure my school treats students the same way. I help our teachers understand that a child who learns best while wiggling or standing is not a “problem child,” but rather a student who deserves every possible opportunity to succeed. When a child struggles to read, I remember that I struggled too, and I encourage teachers to support students in ways that don’t make them feel singled out.

Now in my tenth year as an educator, I know that the full impact of all this doesn’t show up right away. As with JB, sometimes it takes months, or even years, for a student to fully respond. This is not a reason to give up. This is a reason to push forward with more energy each day than we had the day before.

So I work toward the light bulb moments. I wait for the split second where a child finally understands a tough concept or a big idea. They don’t have to say anything. They don’t need to exclaim “aha!” – I just watch their eyes light up as they finally realize they get it. When those light bulbs turn on, I see the effect of my long days and late nights. I see the impact of my teachers’ skillful planning and execution. I see my students’ dedication and focus pay off.

Every Wednesday, JB sees that, too. He comes back to work with the students who may be labeled as “bad,” or “rude,” or even “dangerous” by the world. JB doesn’t see them that way. He knows each child has limitless potential, and he’s there to help them reach it. If I can approach my work each day as JB does, I will call that day a success.