The November 2021 issue of New Orleans Magazine included the following sponsored article on Morris Jeff Community School and how they incorporate mindfulness programming into the school day.

If a middle schooler acts out in class at Morris Jeff Community School, they’re sent to the “mindful moment room” instead of the principal’s office. They’re given a guided meditation instead of a detention. For five to fifteen minutes, they have the space to reset.

As Ryan Ruyle, the middle school principal, explains it, this process allows a child to “just get calm, get breathing, get thinking. And then after carrying out some sort of meditation, then the discussions happen. Like, ‘What happened, what led to the incident? What can you do to fix this?’ It’s tied closely to a more restorative approach.”

Those meditations and discussions are led by Latrice Offray. After working as a teaching assistant at Morris Jeff for years, Ruyle hired her as the middle school’s Mindfulness Facilitator.

“She’s really excellent at listening to the students and trying to understand their perspective. And then she’s really good at also giving perspective, especially if there’s a conflict with another student or conflict with the teacher. She helps the students see the perspective from a different side.”

Offray’s role was created as part of Morris Jeff’s shift to mindfulness and restorative justice. This was an intentional programmatic choice to support their students socially and emotionally and ensure their disciplinary process was equitable and holistic.

It was born over a year ago, when the CEO of Morris Jeff Community School, Patricia Perkins, showed Ruyle some research on the power of mindfulness in students. She wanted to bring mindfulness programming to all three of the school’s campuses.

“We know mindfulness not only helps children feel calm and cope with difficult emotions, but it can also improve academics, increase attendance, and decrease disciplinary incidents,” Perkins explains.

Ruyle dove into the research, eager to plan what mindfulness would look like at the middle school level. He found that one of the leaders in implementing this type of work was the Holistic Life Foundation, which leads mindfulness programming in classrooms in Baltimore, Maryland. In one school Holistic Life worked in, suspensions for fighting dropped in half in one year, and the percentage of 9th graders rising to the 10th grade grew that same year from 49% to 64%. Ruyle got in touch.

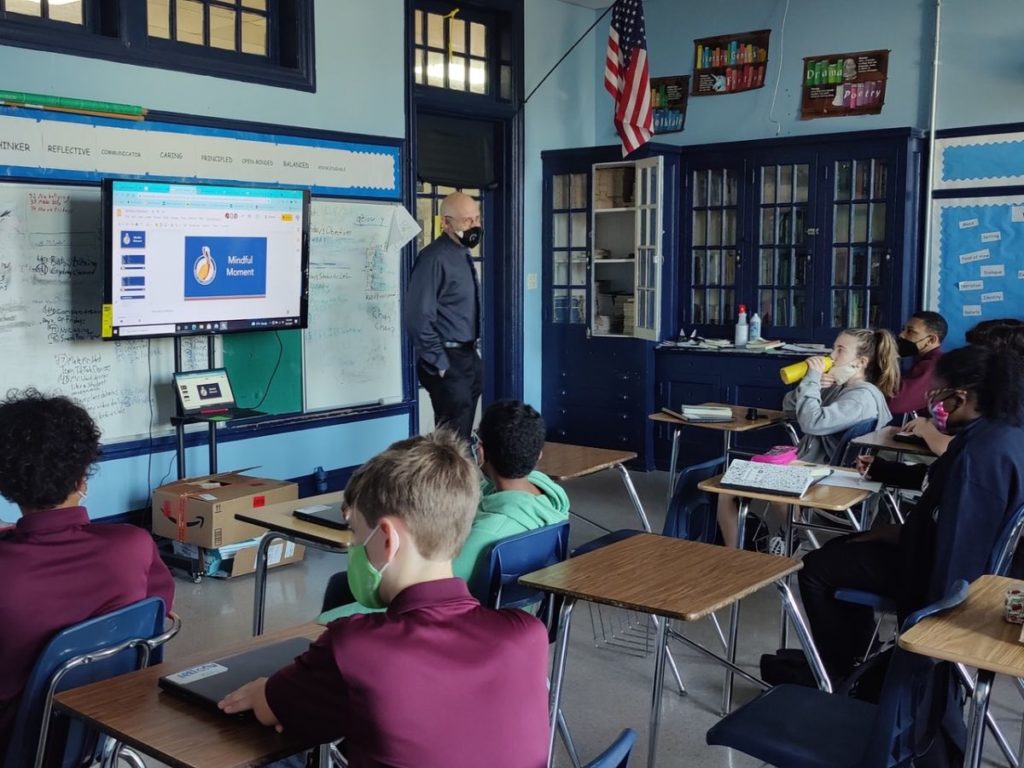

He arranged for the Holistic Life Foundation to train his teachers in their methods last summer.

“You hear that kind of as a buzzword, around mindfulness. But with the Holistic Life Foundation, we actually learned what it is, how to actually teach it to somebody, and then how you use it to de-escalate or help students cope.”

Now, in addition to the “mindful moment” room, students engage in two “mindful moment” meditation sessions each day–one at the very start, and one just after lunch. Shannon Herbert, the Dean of Students, designs the mindful moments meditations and shares them with faculty.

Ruyle says this has changed the way his school looks and feels. Morris Jeff had always been dedicated to social-emotional support and making sure children felt heard and loved, but now there are new structures for that in place.

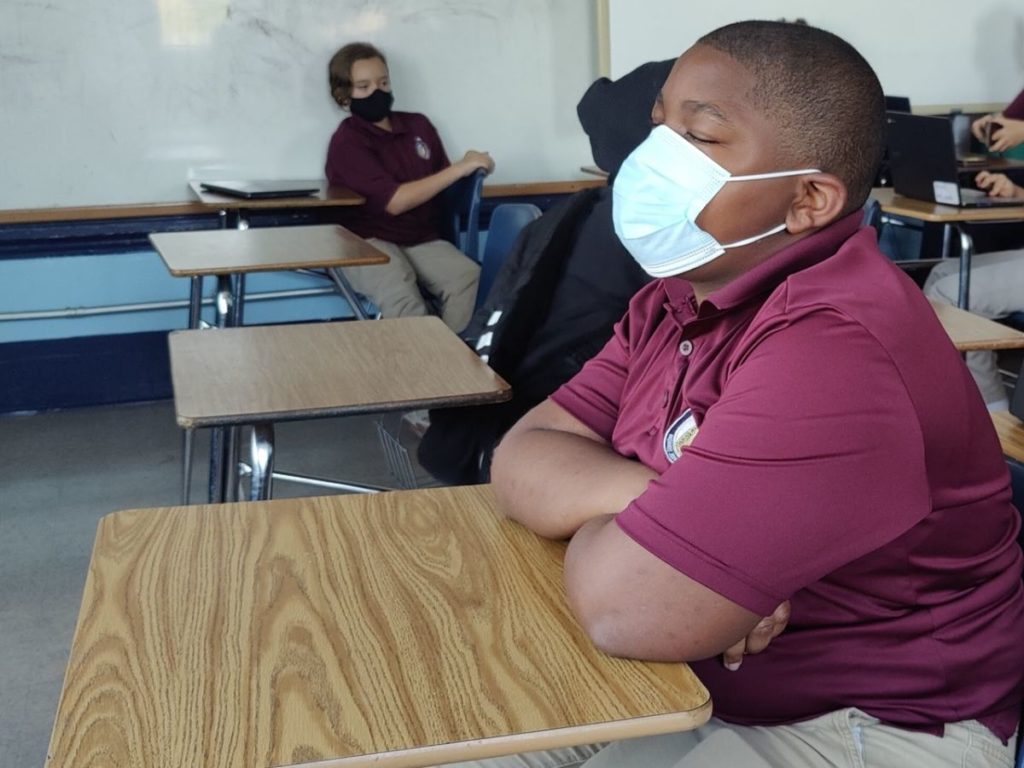

“If you were to come in at the very beginning of the day, he explains, “you’d see a pretty typical middle school, the hustle and bustle of kids getting breakfast, buses running late. But when the bell rings at 7:45, when you walk around, you’re not going to hear much.”

By then, the classes are quietly meditating.

“You might hear some recordings, or teachers, or even students leading meditations or breathing exercises…you might see or hear a meditation going on where they’re doing their deep breathing and working on paying attention to their thoughts, or noticing their feelings.”

Ruyle says he’s seen students use these strategies over the course of the school day. Sometimes, students “refer themselves” to the mindful moment room. They tell a teacher they need to step out because they’re having a strong emotion or problem they need help with, and their teacher texts Ruyle, Offray, and other administrators to see if they can escort the student to the room.

There’s real impact when it comes to discipline, too.

“There’s been a big reduction of kids being sent out during class for issues that usually would have caused an administrative discipline referral.”

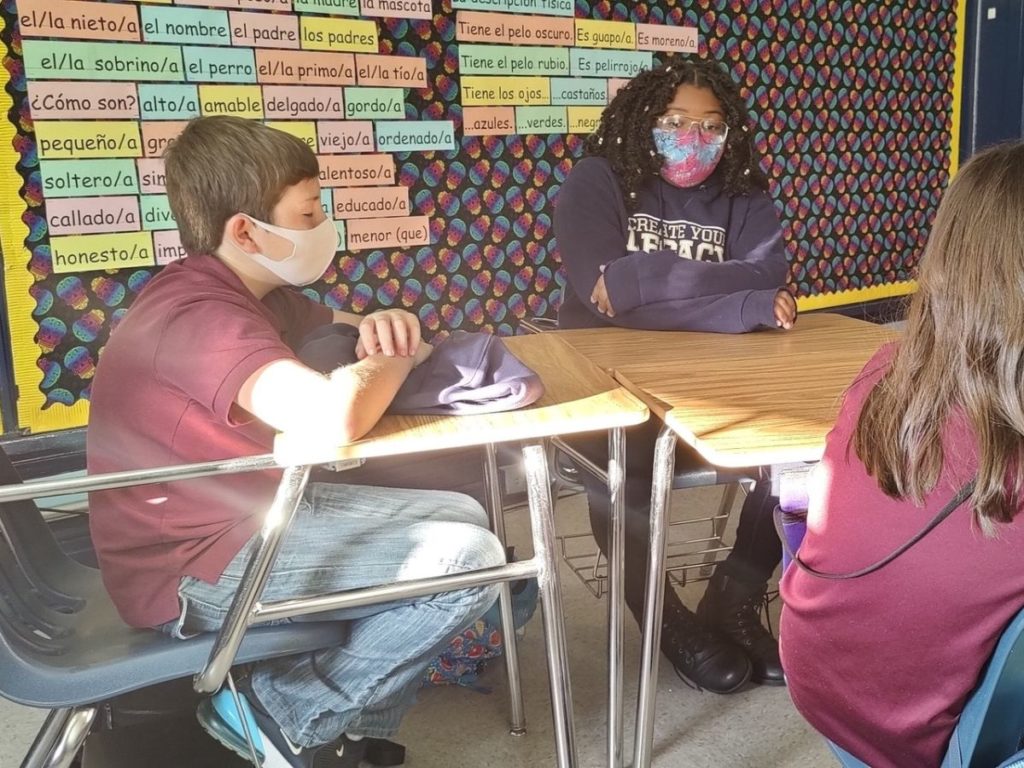

When there’s an altercation between students, they cool down in the mindful moment room, then meet with the Dean to solve the problem together.

This shift in response to discipline in particular has changed the way students and their teachers can relate.

“It keeps relationships much stronger,” Ruyle says. “When a teacher has to give a student a traditional disciplinary consequence, it can damage the relationship and often takes a lot to rebuild. In this particular case, it’s not seen as discipline or punitive. For kids and teachers, it’s seen as ‘I want you to come back, but I want you to come back when you’re in a calm space that’s focused on learning.’”

When Hurricane Ida hit, Ruyle knew mindfulness practice might help students cope, but he and his team also knew they, and all of our community, needed more. Counselors reached out to families, checked in on what they needed and if they’d been displaced. They continued that outreach while students were off campus, then made sure any students that needed support once class started up again were connected to resources.

And of course, they began their days with meditation, just as they had before the storm. It was consistent, calming, and centering. And if they were having strong emotions that they struggled to deal with, there was always the mindful moment room.

“They can basically relax, meditate, and breathe,” Ruyle says, “and kind of catch their breath before returning to work.”