By Byron Goodwin, Director of Transition and Community Engagement, and Zelda Smith, Director of Curriculum and Instruction at Travis Hill Schools

Imagine a school where students are making art, playing chess, doing science experiments, and reading great literature. Imagine a school where teachers use restorative practices and students get a chance to reflect and speak their minds. Here in New Orleans, that school exists—within two local detention centers.

Travis Hill Schools are located inside the Youth Study Center and the Orleans Justice Center, as of 2016 and 2017, respectively. They operate through a contract between the Orleans Parish School Board (OPSB) and the Center for Educational Excellence in Alternative Settings (CEEAS), which manages Travis Hill. At the Youth Study Center, which is run by the city, we teach around 40 students aged 13-18 years old, and at the Orleans Justice center, we teach around 55 students between 16 and 21.

At Travis Hill Schools, we listen to our students. In order to support these young people, we have to hear what they’re saying instead of telling them what they need.

At Travis Hill Schools, we listen to our students. In order to support these young people, we have to hear what they’re saying instead of telling them what they need.

This is what our students tell us: they want to learn. They look forward to the academic day. They want our time together to feel as much like “real school” as possible, even if when they leave their classes, they’re still inside a jail.

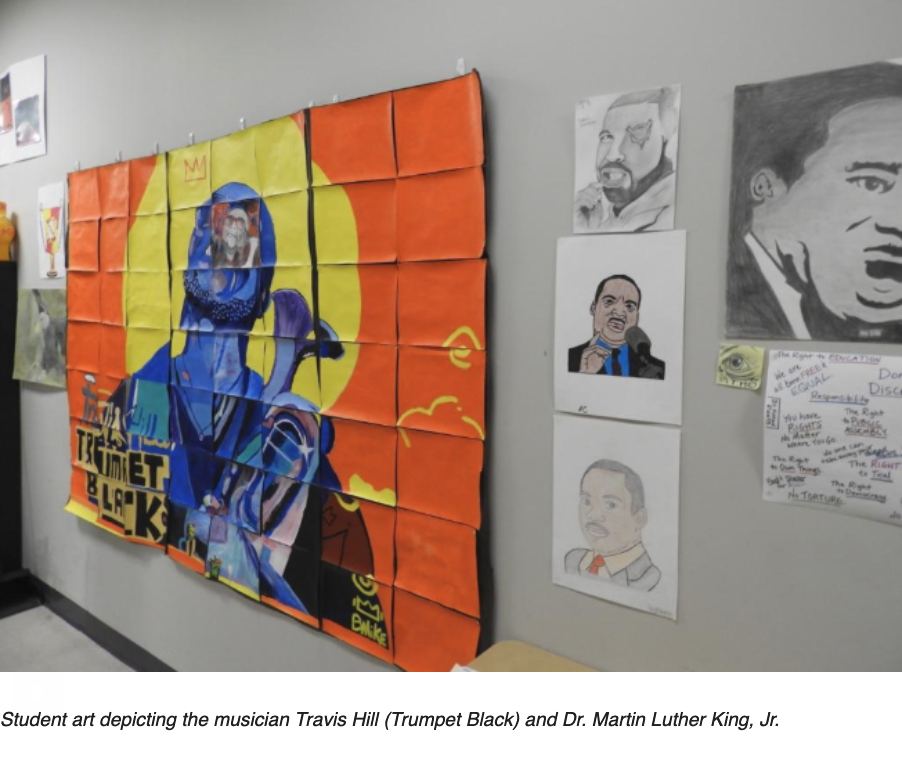

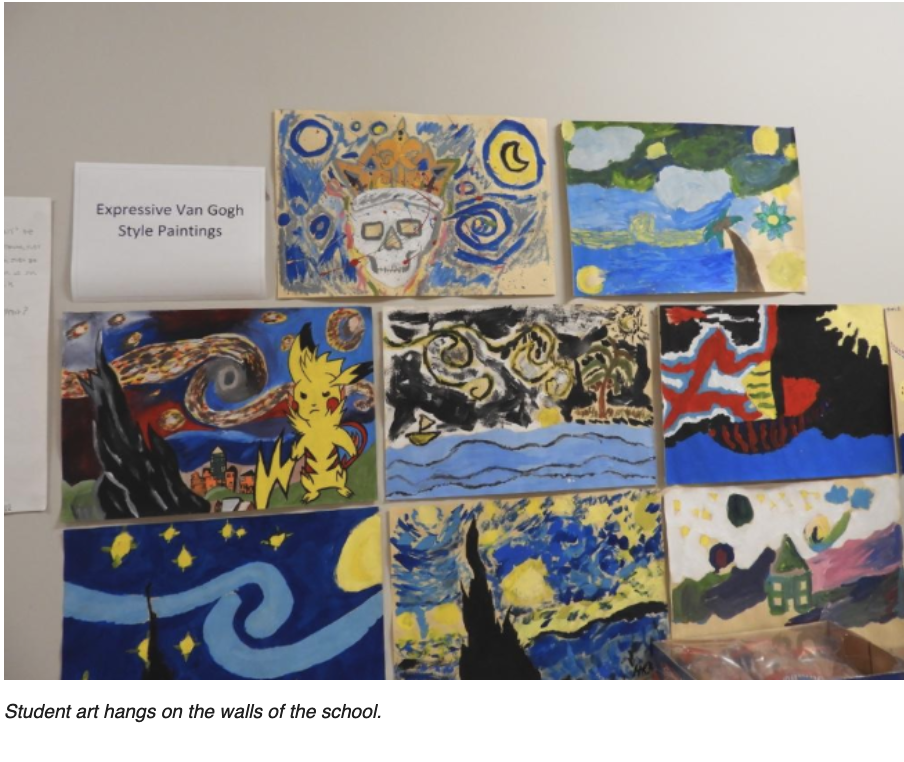

Our schools are “real schools.” Our students take the usual classes, like Algebra and English, but they also have art, music—and even briefly, at their request, Home Economics. We’ve seen real results, too. Travis Hill Schools were in the top 5 citywide for highest “top growth” percentage in ELA, and had the highest “top growth” percentage for ELA and Math combined across all the alternative schools in New Orleans.

Unlike many other schools in detention centers nationally, our students earn real diplomas when they graduate. We have full ceremonies that their peers and families can attend, alongside special guests like school board and city council members, Superintendent Henderson Lewis, Jr., and Mayor LaToya Cantrell. We have had 11 graduates so far.

Unlike many other schools in detention centers nationally, our students earn real diplomas when they graduate. We have full ceremonies that their peers and families can attend, alongside special guests like school board and city council members, Superintendent Henderson Lewis, Jr., and Mayor LaToya Cantrell. We have had 11 graduates so far.

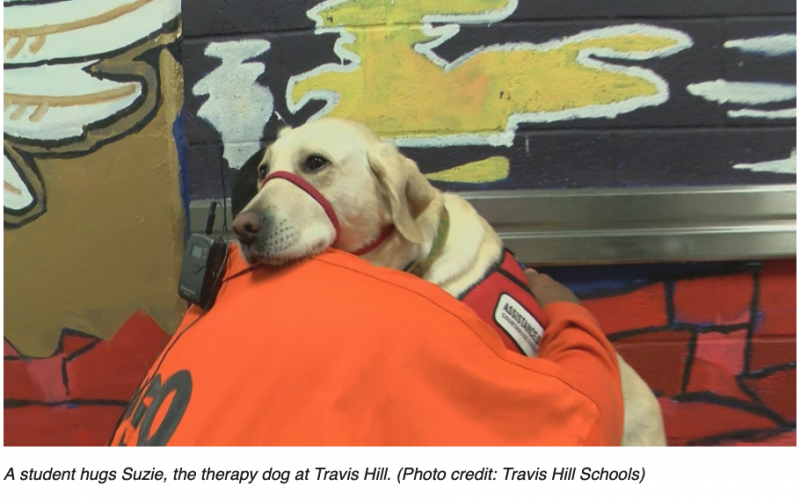

The students of Travis Hill are all pre-trial and haven’t been convicted of anything. Even so, the wider world judges young people like the ones we teach. Some see our students as inmates, but we know them as children and young adults, sons, brothers, daughters, and dads. At Travis Hill, we watch as they play hide-and-go-seek for a break. We see them fall in love with our therapy dog, Suzie—students who have had to act “tough” for so long finally feel safe enough to let down their guard. For some, it takes coming to jail to be able to act like a child. These are young people who had to become adults too quickly in the world outside—they carried the weight of responsibilities far beyond their age. Now, they can be ten, eleven, eighteen. With us, they make their way through ups and downs of childhood and adolescence, laughing and playing, learning and growing in ways they hadn’t given themselves permission to before.

The students of Travis Hill are all pre-trial and haven’t been convicted of anything. Even so, the wider world judges young people like the ones we teach. Some see our students as inmates, but we know them as children and young adults, sons, brothers, daughters, and dads. At Travis Hill, we watch as they play hide-and-go-seek for a break. We see them fall in love with our therapy dog, Suzie—students who have had to act “tough” for so long finally feel safe enough to let down their guard. For some, it takes coming to jail to be able to act like a child. These are young people who had to become adults too quickly in the world outside—they carried the weight of responsibilities far beyond their age. Now, they can be ten, eleven, eighteen. With us, they make their way through ups and downs of childhood and adolescence, laughing and playing, learning and growing in ways they hadn’t given themselves permission to before.

So we see our students not for what they’ve been arrested for, but for who they are as people. We also understand that external factors often play a huge role in shaping their path to us at Travis Hill. Our students have experienced a great deal of trauma; during Hurricane Katrina, the oldest were seven or eight years old, and some of the youngest were just about to be born. Many of our students have lost friends and family to violence, causing deep grief and fear. The Institute for Women and Ethnic Studies Center’s “In That Number” campaign reports that 54% of the New Orleans youth they surveyed had lost someone close to them to murder.

But when we first meet our students, we don’t know what they’ve been through or what they have seen. As educators, it’s our job to understand them and help them cope with their struggles in healthy ways. Mental health is a real concern for many of our students, but for some, the real problem isn’t mental health, it’s poverty. These young people experienced hunger and homelessness, or had to live with no consistent lights or water. That takes a serious toll on a child. And when they join us at Travis Hill, they are all pre-trial, so they are facing an uncertain future and often a great deal of fear.

But when we first meet our students, we don’t know what they’ve been through or what they have seen. As educators, it’s our job to understand them and help them cope with their struggles in healthy ways. Mental health is a real concern for many of our students, but for some, the real problem isn’t mental health, it’s poverty. These young people experienced hunger and homelessness, or had to live with no consistent lights or water. That takes a serious toll on a child. And when they join us at Travis Hill, they are all pre-trial, so they are facing an uncertain future and often a great deal of fear.

By acknowledging the pain of our students’ situations, we help them feel safe enough to open up and heal. We had one student, Eugene, who was distant and disengaged most of the time. But we knew some of his background, like the fact that his grandmother was working overtime at IHOP to pay for his attorney. Eventually, the legal bills left her homeless, and even then, she kept working to pay the lawyer that might help get her grandson out. One day, Eugene was acting out in class, and we pulled him aside and said, “Look, we know your grandmother is out there working so hard for you, and you’re in here cutting up.” Eugene broke down and cried for an hour. We had given him the opportunity and the permission to feel, and that was powerful for him. From that day onward, Eugene’s behavior changed, and soon after, he was released. He’s now at a local charter school. Every time we run into him, now, he’s a joy to see.

It’s our job, as a school and a society, to help students like Eugene, not condemn them. We strive to help our students feel supported, respected, and academically engaged. But we can’t do this alone. Outside of our walls, we need more resources to support young people in difficult situations. Our students need tutoring, mentoring, mental health services, and the chance to connect with their peers. We need more parks for them to play in, so they can be children again. We need teachers and school leaders who understand trauma and are trained in restorative justice techniques.

For now, we will continue to do everything we can to help students feel hope in dire circumstances. And every day, they show us their great capacity to work toward and dream of a better future. In a mural at the Orleans Justice Center that our students helped paint, the words “Travis Hill School” emerge from behind the New Orleans’ skyline. The black superdome and city buildings are lit with highlights of yellow and red. Right down the middle, an enormous dove opens its wings, and above it, two clenched fists hold either side of a broken chain. The talent, hard work, and love we see from our students fuels us each day. It is our urgent hope that others will see them as we do—as brave, brilliant young people who have so much to contribute to our city and our world.

Note: “Eugene” is a pseudonym.