Nicole Saulny has been an educator in New Orleans Public Schools for over a quarter-century. Her father was an educator here for 40 years, and her mother taught for 30 years, most of which she spent in the same building where Saulny would later be principal. Saulny also has two daughters. One is a recent graduate of New Orleans public schools and the other is a current student.

So New Orleans public schools aren’t just Saulny’s job. They’re her family, and she thinks of all her students as part of her family, too. Her father instilled that in her from her very first day as an educator.

“The first day I walked out of my parents’ home to go teach, my dad said to me, ‘you must view every child as your own, or get out of the profession.’”

She’s been following his advice ever since. “Because the same thing that I want for mine that I gave birth to, I want for the children that I am serving,” she says.

Saulny encourages her team to think the same way, whether it’s their own children, those of family, or friends – or even Saulny’s daughters. “I used to say all the time, ‘pretend that you are teaching my daughters and I’m sitting on your shoulders watching,’” she says.

Saulny’s team has expanded lately. After serving as the principal of Esperanza Academy for almost a decade, she stepped into the role of Chief Schools Officer (CSO) at Community Academies of New Orleans (CANO), the charter network of which Esperanza Academy is a part.

When Myrialis King, who leads CANO, asked Saulny to consider being the CSO, Saulny was skeptical. She hadn’t heard the acronym before. “I was like, ‘’what is that? I don’t know anyone with that particular role,’” she recalls.

As she learned more, she was interested. The Chief Schools Officer supports the principals of all the schools in a charter network. At CANO, that means coaching the leaders of Foundation Preparatory Academy, Lafayette Academy Lower School, Lafayette Academy Community Middle School, and Esperanza Academy. As much as Saulny loved being the principal of Esperanza Academy, she was interested in having a different type of impact.

She took the role this summer, but her outlook on the work hasn’t changed. Working for a school, says Saulny, means being a steward of that school, no matter your official title.

“If there’s a mop in the corner,” she says, “and a spill on the floor,” she’s not going to call someone else to clean it up. She’ll pick up the mop. “I would never tell a teacher or staff member to do something that I’m not willing to do.”

When it came to leading principals, Saulny was prepared for the work both from her experience as an educator, and because she has been an E3 Fellow with NSNO for the past year and a half.

The E3 program provides professional development for education leaders interested in working at the charter organization management level. It also offers a small community of fellow education leaders who are passionate about their work.

“I tell people all the time, it is one of the best programs that I’ve ever been in. Not only from the relationships I’ve built with my fellow members, but just the wealth of knowledge that I’m receiving. They’re pushing our thinking, they’re championing us,” she says.

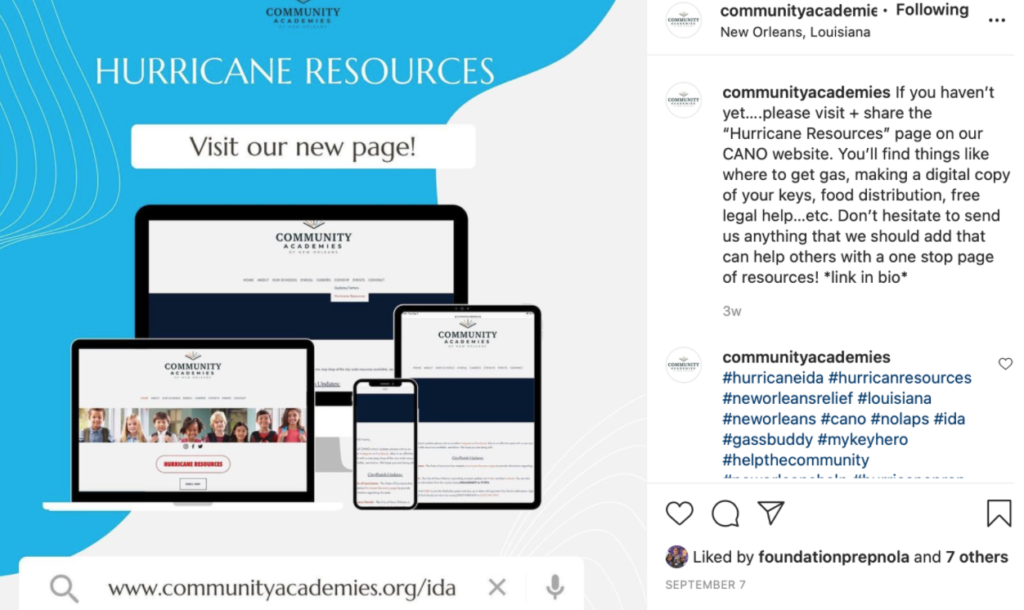

The E3 fellows champion one another’s work, too. This is critical, especially when disaster strikes. When Hurricane Ida hit, the E3 leaders were quickly corresponding on a text message thread, connecting around what resources they’d found and how their schools had fared. The collective brainstorm helped Saulny determine what steps she would take.

She and her team reached out first to her teachers, knowing they needed to feel safe and supported in order to help their students feel that way. They reassured teachers that even if it took some time to get school back up and running, the jobs they loved weren’t going anywhere. They asked them to return to campus two days before students.

“It would be very difficult for us to just say, ‘hey, students and teachers return all on the same day and jump right back into instruction.’ We have to look at not only the children’s emotional needs, but also as well as the staff’s emotional needs,” Saulny says.

There were logistics to take care of. For instance, the Esperanza building had been severely damaged, and its students would be attending school from the Lafayette building until it was repaired. The schools also decided to extend their school day between fifteen and twenty minutes in order to make up for the learning time lost to the storm.

Teachers and social workers made “wellness calls” to every family. They asked how children were doing. They asked family members how they were doing, too.

“If the caregiver is not in the right state of mind, then the children notice that, no matter how much a caregiver, a parent or guardian will try to mask it or protect them,” Saulny says. “Children are very intuitive. So it’s important that we make sure that our entire families were equipped and ready to return.”

The CANO team had gathered a list of resources from across our community and they shared them with families – from where to get free healthcare to where to get free food. Saulny has always sought to connect her students to resources across the city.

To do so, she talks about her schools to anyone who will listen. Before the pandemic, she lined up free yearly teeth-cleaning for 400 of CANO’s students by talking about her schools with her dentist. Opportunities to engage support are everywhere.

“It could be simply standing in a Starbucks line, it could be a church member, you never know who you’re having conversation with and how they can add value to your organization.”

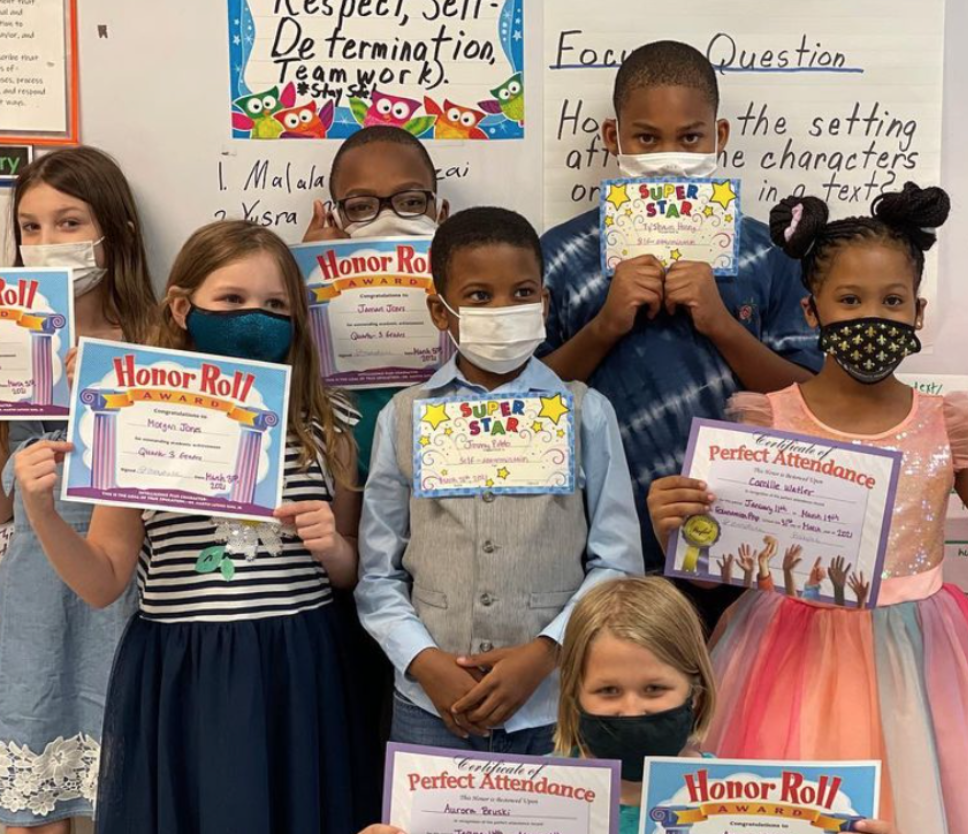

Saulny wants people to know not just how they can help her schools, but she also wants them to know how her schools help their community. She is proud of her students, her teachers, and her team. She believes in sharing that.

“You have to speak and champion your organization and get the word out, to make sure that people are knowledgeable of the great work that is going on in our schools.”