This summer, we spoke with Dwana Caliste of Camp Thrive. With the school year about to begin in this new and different context, we want to highlight how one camp adjusted to the limitations of this moment and provided a safe, meaningful experience for campers.

At 2:30PM, when Camp Thrive is ending for the day, “Boots” is having too much fun to go.

“Boots is the nickname we gave her, because on the first day of camp she wore glitter boots. She’s five, she’s missing all these teeth, and she’s the camp boss,” explains Dwana Caliste, who leads the camp.

“She is always asking what I am doing and why she can’t do something. We will all be getting ready to leave and she’s like, ‘I’m not leaving, nobody’s going to make me.’”

For Boots, and so many of her peers, Camp Thrive is a joyful respite in stressful times. Camp Thrive is a free camp run by Thrive New Orleans and partners with the New Orleans Recreation Department (NORD).

Camp Thrive, like all summer camps nationwide, looks different this summer than it ever has before. Everyone gets a temperature check before the day can begin, and the campers are clustered in smaller groups. Parents can no longer enter the building and adults wear masks. The camp administration followed detailed procedures to ensure staff and campers alike stayed safe.

“But the routines of camp have stayed the same,” Caliste explains. “In a time like this, it takes a lot of stress off the camper to see the same faces each year and each day and have the same routine of care.”

While in previous years, the highlights of camp were taking field trips and going swimming, this year, any travel has been virtual.

“The five and six year olds went to Italy the other day,” Caliste says. “We’ve been taking virtual field trips. We’ve been all over the world in two weeks online, through video tours.”

Outside of those trips, the daily schedule is the same as it has been each year. Campers come in for breakfast at eight, and at nine, they have Harambe.

“Harambe means come together in Swahili,” says Caliste. “We sing and dance to get energy going for the day.”

After Harambe, the campers practice for a finale performance they build up to over the course of camp. Then they have “integrated reading time,” broken up by ages. Caliste builds the curriculum herself using students’ report cards. She bases the material for the summer on what students need to practice most, and she connects the reading to relevant topics and ideas. During the week before Junteenth, for instance, the readings and lessons were structured around the holiday, and led up to a camp-wide Juneteenth performance.

After their lessons, campers get “brain breaks” during which they can decompress on their own, make some art, or engage in group activities, like playing volleyball or musical chairs.

“Over the summer, you lose a lot of what you learn during the school year, so we want to give them opportunities to learn—but then we have brain breaks, which gives them a choice of what to do. We don’t want them to have every second planned out and be overwhelmed,” Caliste says.

Then, they might have karate, dance, water-play, or free play. In lieu of the swimming trips of years past, they now have water balloons, slip-and-slides, and a sprinkler set for kids to play in.

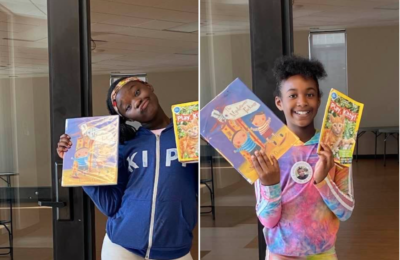

The last structured activity of the day comes right before lunch. Read Aloud involves a special guest reader who comes and reads a book to the students all at once. These might be family and friends of the Thrive team, older campers, community members, or local leaders. In June, Orleans Parish School Board member Ethan Ashley visited and read campers a book about music. He brought a friend who played the trumpet along with him; the friend played the trumpet when there was music in the book.

Caliste runs the camp with eleven counselors. Most are college students on summer vacation, and many attended camp themselves years prior. The majority are graduates of G.W. Carver High School, where Ms. Caliste teaches.

Caliste’s own first job was working at camp when she was sixteen. She has not missed a single summer since. She has even written a book about some of the mindsets and ideas she wants camp volunteers to bring to their visits.

“You aren’t going to get rich doing this. You do it because you see the good in kids and you want them to reach their full potential.”

The first summer after Hurricane Katrina, Caliste and another former counselor, Oscar Brown (who is now the executive director of Thrive) ran camp out of a house in the Desire community. Neither got paid that year, but they knew they needed to keep camp going.

Now, two decades into her work with Camp Thrive, Caliste is still loving her role—even if the campers don’t quite know what it is.

“They don’t think about my title. They know I’m the lady in the circle with them, screaming as loud as them with Harambe. I’m the one playing musical chairs with them. I’m the one teaching them double dutch. That’s what I really want them to remember—‘she taught me how to double dutch.’ When they see me, sometimes I’m cleaning the bathroom, sometimes I’m reading with them, sometimes I’m giving directives. When they see me at the supermarket during the year, they say I’m the summer camp lady, and that’s what I am. I try not to get caught up in the hoopla of what your title is.”

To students’ families, Caliste is a partner. She gets their feedback formally twice a summer, before and after camp starts, and informally all year long. And though COVID-19 means she can no longer welcome them inside the building, she invites them to join in double dutch or step into an outdoor activity.

“In the hustle and bustle of life, kids don’t always see their parents in that type of light,” she says.

But Caliste points out that students feel connected to her as part of a family, too.

“I think kids see family in me. I look like some of their mamas and aunties. I talk like them and walk like them. They think, ‘I can really be Ms. Dwana,’ but I feel like they’re going to have better Dwanas. I know for a fact that they’re going to be better than me because of the foundation that I lay for them. I just get to be a part of the journey.”

She has already seen her campers grow into powerful young people—and she knows they will continue to.

“Now, kids will share pictures with me of their college degrees and say, ‘look at this!’ and I say, ‘I knew that all along.’ I’m excited, but I’m not surprised. Because when I see the kids at camp, I see the greatness inside of them.”